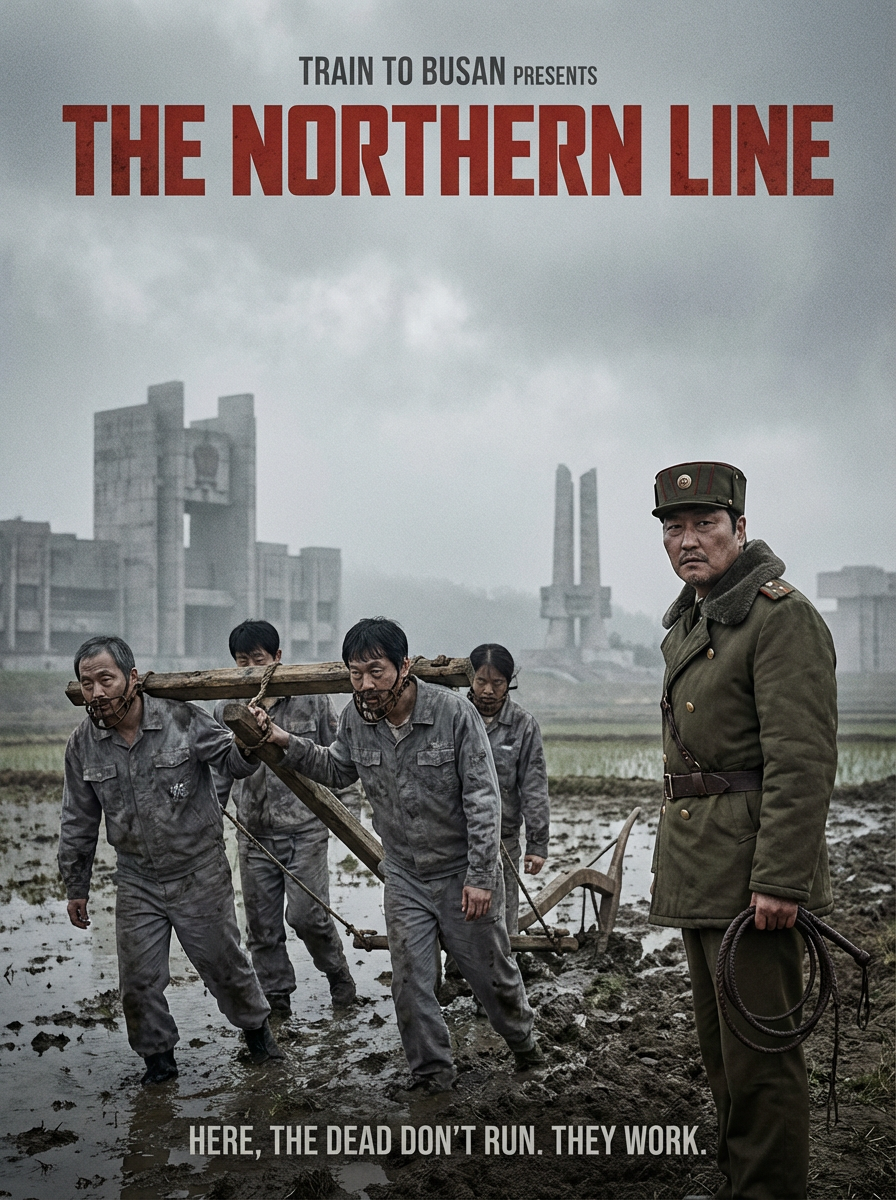

THE NORTHERN LINE

The Northern Line is a film that doesn’t just depict suffering; it methodically, mercilessly metabolizes it, transforming the prison-camp thriller into a work of profound physical and existential horror. From the visionary dread of Train to Busan director Yeon Sang-ho, this is not a zombie film in any conventional sense. It is a glacial, suffocating autopsy of dehumanization, where the monstrous is birthed not from a virus, but from the absolute extraction of hope. Set within the frozen, soul-crushing architecture of a secret labor camp, the film presents a world where the barbed wire is as much psychological as physical, and the real prison is the ceaseless, back-breaking labor designed to erase identity itself. Gong Yoo, in a performance stripped of all vanity and star power, embodies this erosion with devastating clarity. As the high-ranking defector, his initial defiance is a flame quickly smothered by the sheer, overwhelming weight of the system—a system where the only currency is pain, and the only escape is the release of death, or something far worse.

The film’s visual and atmospheric language is a masterpiece of oppressive minimalism. The palette is a brutalist poem of industrial grays, mud-black filth, and the blinding, sterile white of endless snow under gun-tower spotlights. Cinematographer Lee Hyung-deok frames the ceaseless, Sisyphean labor—the pulling of impossible loads, the pounding of frozen earth—with a rhythmic, almost liturgical cruelty that immerses the audience in a state of shared exhaustion. The horror here is systemic, ambient, and utterly plausible until it begins its terrifying metamorphosis. The “outbreak” is the film’s brilliant, sickening twist: the weakest prisoners, their bodies and spirits fully broken, do not die. They change. They become silent, hollow-eyed automatons who work with relentless, inhuman efficiency—not running amok, but becoming the perfect, unquestioning laborers. This is the camp’s final, logical evolution, and it poses a question more terrifying than any sprinting ghoul: Is rebellion against a fate that strips you of your soul even possible, or is the ultimate victory for the system to turn you into its most compliant cog?

Yeon Sang-ho masterfully uses this setting to explore the corrosion of rebellion and the ambiguity of resistance. The whispers of an underground network, the flicker of solidarity in a guard’s eye, the discovery of a hidden message—all the classic tropes of the prison-break genre are present, but they feel fragile, possibly even orchestrated. The film’s central, paralyzing tension lies in wondering if any act of defiance is genuine, or merely another layer of control engineered by the unseen powers “from the shadows.” The final act descends into a chaos that is both visceral and deeply philosophical, as the lines between prisoner, guard, and the hollowed-out “workers” collapse into a desperate scramble for meaning in a place designed to annihilate it. The Northern Line is an uncompromising, emotionally shattering experience. It is a film that holds you in a state of breathless, chilled dread from its first frame to its last, offering not catharsis, but a sobering reflection on the limits of the human spirit. It asserts that true horror isn’t found in the supernatural, but in the meticulously engineered machinery that seeks to reduce a person to a thing—and the terrifying new shapes a thing might take to survive.

Watch trailer: